By Stephanie M. Foote and Brent Drake, The Gardner Institute

As a member of the Strong Start to Finish network, the Gardner Institute is committed to have every student pass credit-earning gateway courses, including English and math, in their first year of college. Gateway course redesign is one of several strategies to achieve this goal. Course redesign can be a daunting task for faculty, yet it is essential to engage in continuous course improvement. Redesign is particularly important in gateway courses to ensure all students can be successful. While some have a narrow definition of gateway courses — focusing on English composition and the first college math courses — we prefer a broader view that includes all lower division, high-enrollment courses that serve as a required gateway course into the discipline. Often gateway courses have higher rates of D, F, W and I (or incomplete) grades, and serve as gatekeepers, preventing students from progressing to and through the general education curriculum and/or program of study associated with a particular major. Since 2013, the Gardner Institute, has provided faculty, staff, and administrators with support in an evidence-based gateway course redesign process, and as a result, more than 318 courses, across colleges and universities in the United States have been redesigned.

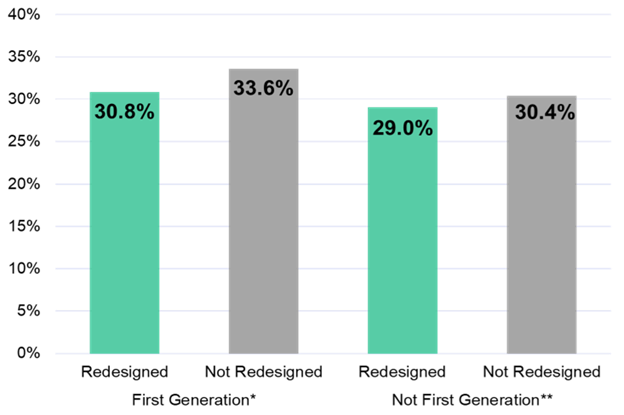

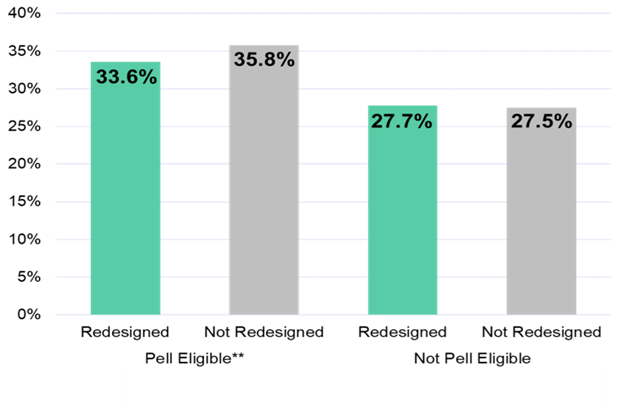

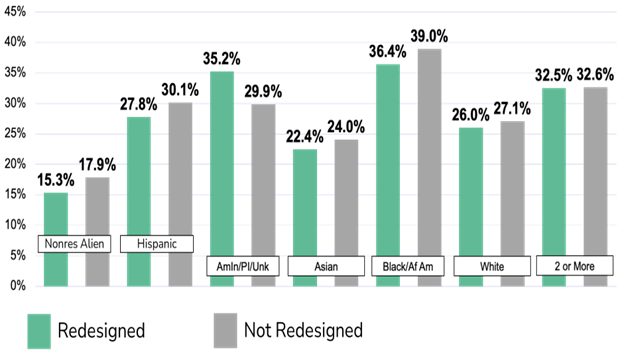

Over a period of three years, 29 different courses that span across a variety of disciplines (e.g., accounting, biology, English, history, math, political science, psychology, and science courses like Biology and Chemistry) were redesigned by faculty at 10 institutions in the University System of Georgia. Through this process, positive results (lower rates of grades of D, F, W and I) were found in 22 of the courses. When examining all 29 courses, compared to non-redesigned sections of the courses, the redesigned sections had a 1.8% lower D, F, W and I rate. Furthermore, the impact on success for students with historically marginalized identities is notable, as Figures 1-3 illustrate.

Figure 1. D, F, W and I Rates for Redesigned and Non-Redesigned Courses by First Generation Status

Figure 2.D, F, W and I Rates for Redesigned and Non-Redesigned Courses by Pell Eligibility

Figure 3. D, F, W and I Rates for Redesigned and Non-Redesigned Courses by Race/Ethnicity

While faculty involved in the course redesign process employed a variety of approaches in the redesign of their individual courses, predominantly, the redesign involved the following:

- Pedagogical changes — Incorporating active and experiential learning, teaching study strategies, using metacognitive approaches, and fostering social cognitive development like growth mindset

- Curricular changes — Focusing on the use of inclusive pedagogies and curricula (e.g., including diverse perspectives and sources in course content and assignments).

- Course structure changes — Involving changes in modes and modalities, course access, assessment, design and use of Open Education Resources.

- Integration of academic success initiatives — Including academic advising or coaching, early alert, embedded peer support, supplemental instruction or high-impact practices.

Of these approaches, pedagogical changes were most common, but equally popular were changes involving the integration of academic success initiatives or high-impact practices.

A case study anthology series published by the Gardner Institute documents the gateway course redesign work of the faculty and staff at seven of the ten University System of Georgia institutions involved in the first cohort. Following, we focus on examples from the redesign of Principles of Chemistry I and American History to 1877 featured in the second volume of the anthology series.

American History to 1877 (HIST 2111)

The HIST 2111 course redesign at Georgia Highlands College focused on five specific areas that guided the faculty in a comprehensive redesign of the course, including:

- The adoption of an Open Education Resource.

- The use of in-class activities that activated metacognition (exam wrappers, note-taking pairs, etc.).

- The implementation of an early warning policy and process.

- The development of an adjunct liaison position to support part-time faculty teaching the course.

- The adoption of a new curriculum aimed at fostering historical thinking skills through active learning.

As a result of these changes, one semester after implementation, D, F, W and I rates in redesigned sections were 2 percentage points lower than in non-redesigned sections, and the D, F, W and I rates dropped by 2% (by the second year of implementation) and by 8% from the highest rates in 2014-15.

College Algebra (MATH 1111)

Similar to the approaches used in the redesign of HIST 2111 at Georgia Highlands College, faculty at South Georgia State College employed a variety of pedagogical approaches to improve student outcomes in MATH 1111. Specifically, faculty incorporated discussion boards, tasks aimed at engaging critical thinking skills, and movies about math to help students both learn essential concepts and skills to be successful in the course and to evoke an appreciation for math in everyday life. Critical thinking exercises and assignments engaged students in the use of multimedia as they watched videos of math problems solved incorrectly, culminating in an assignment that invited students to record themselves creating a math problem with an error. Student response to the assignments was favorable.

Conclusion

The course redesign work described here largely occurred during the 2020-21 academic year, as faculty, students and staff were grappling with myriad challenges associated with the global COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, faculty found ways to innovate as they centered students and student success in the redesign of gateway courses across the disciplines. Faculty involved in this work received support and professional development from their institutions, the system office, and through the Gardner Institute’s Teaching and Learning Academy where they learned about approaches to gateway course redesign that is inclusive. While there are many takeaways from our work with faculty in the University System of Georgia, importantly, providing faculty, full- and part-time, with opportunities to engage in evidence-based gateway course redesign can positively affect student success rates in these types of courses. Given the outcomes of the gateway course redesign work we have supported, we encourage all institutions to consider how they can both engage in gateway course design and support faculty in that process. To get started in this work, we encourage faculty and staff identify gateway courses at their institution and collect disaggregated academic success rates (grades of D, F, W, or Incomplete) in these courses to examine which student groups are completing their gateway courses and which are struggling.